December 9, 2025

Insights Without Animals: Leveraging Human-on-a-Chip & PBPK Modeling

This webinar will explain how to use NAMs like organ-on-a-chip and PBPK modeling for innovative, ethical drug development insights without animals.

Piet van der Graaf

Senior Vice President and Head of Quantitative Systems PharmacologyPiet van der Graaf, PharmD, PhD is Senior Vice President Applied BioSimulation at Certara, Professor of Systems Pharmacology at Leiden University, and Professor of Pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Previously, he was the Director of the Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research and held leadership positions at Pfizer in Discovery Biology, DMPK and Clinical Pharmacology. He was the founding Editor-in-Chief of CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology before becoming Editor-in-Chief of Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Piet received his doctorate training in clinical medicine with Nobel prize laureate Sir James Black at King’s College London. He was awarded the 2024 Gary Neil Prize for Innovation in Drug Development from the American Society of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (ASCPT) and the 2021 Leadership Award from the International Society of Pharmacometrics (ISoP). Piet is an elected Fellow of the British Pharmacological Society and has published >250 articles in the area of quantitative pharmacology and drug development.

Frequently asked questions

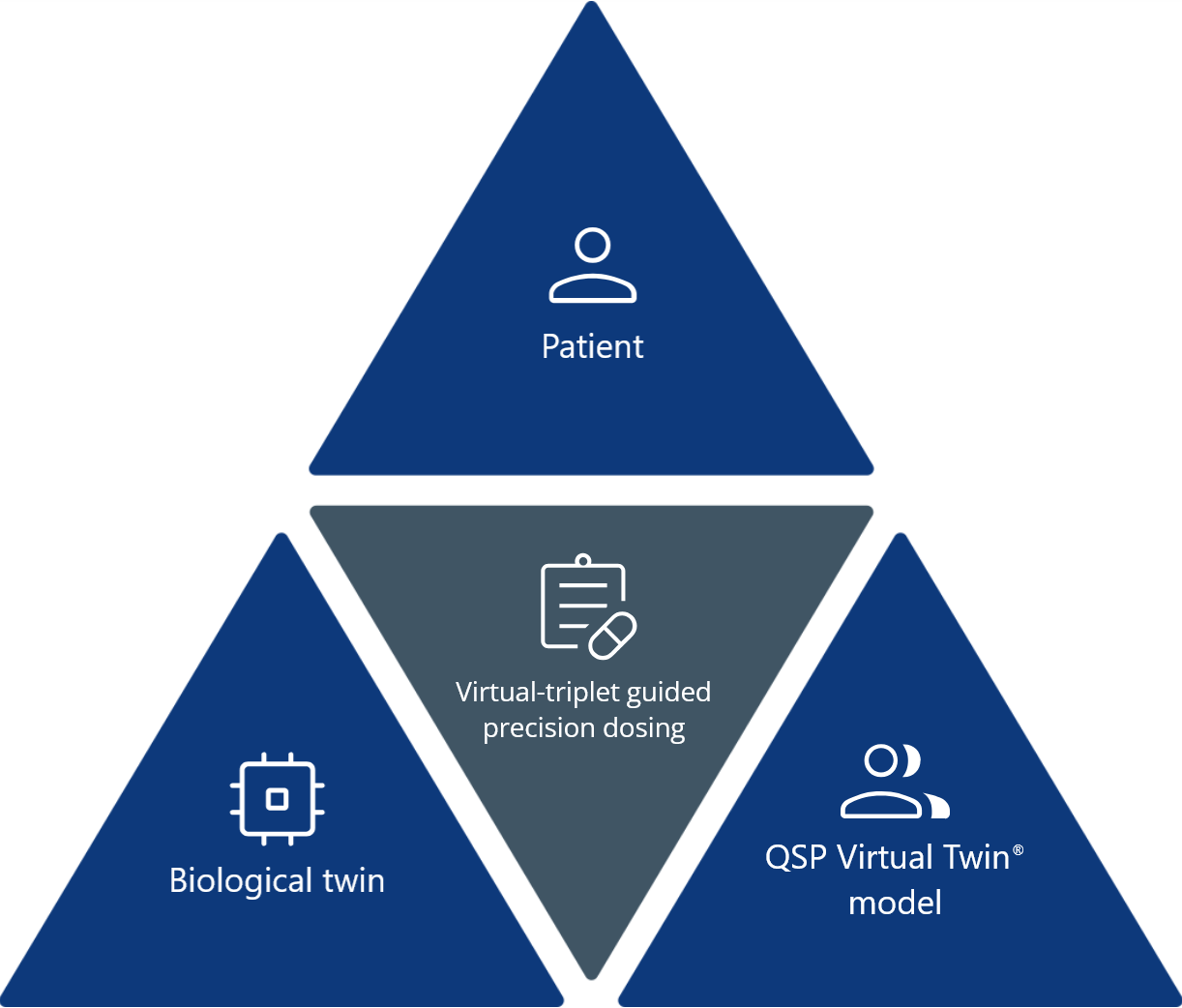

What is a virtual triplet in drug development?

A virtual triplet connects the following three elements into a single framework:

- The patient: An individual with unique biology.

- The Virtual Twin models: Computational models such as PBPK and QSP.

- The biological twin: An organ-on-a-chip derived from patient cells or engineered to replicate human physiology.

Together, they enable real-time feedback between in silico predictions and lab-based results, improving accuracy in dosing, efficacy, and safety assessments.

Why are virtual triplets important for rare disease and pediatric trials?

In populations where patient samples are limited, virtual triplets supplement scarce clinical data with simulations and organ-based experiments. This helps researchers make confident dosing and safety decisions while minimizing the need for animal or large-scale human testing.

How do PBPK and QSP modeling support virtual triplets?

PBPK predicts how drugs move through the body (exposure), while QSP models how drugs affect biological systems (response). Together, they form the computational backbone of virtual triplets, guiding organ-on-a-chip experiments and improving translational accuracy.

Contact us