January 16, 2026

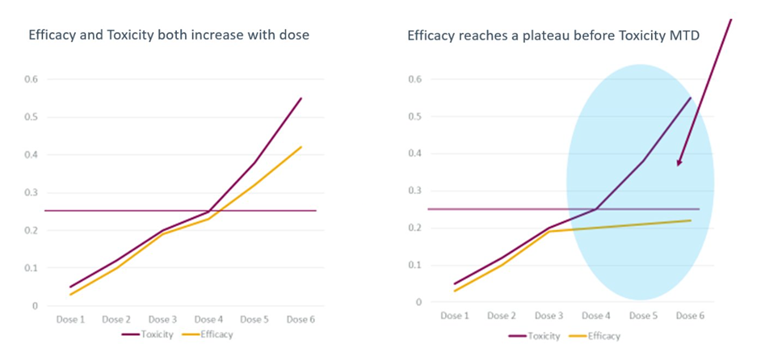

Figure 1. The Project Optimus dose optimization guidance changed how we approach drug development and dose justification. The left figure shows dose escalation for a traditional cytotoxic drug where efficacy and toxicity increase in a roughly parallel manner. The right figure depicts dose escalation in a biologic or targeted therapy. The blue shading reflects doses where the dose response for efficacy and toxicity have diverged. Further increases in dose will yield little increased efficacy, but toxicity may continue to increase.

Adaptive Trial Design for Phase 1 Dose-Finding Studies.

See how adaptive design can help optimize your next oncology trial, strengthen dose selection, and align with the FDA’s evolving standards under Project Optimus. Watch our webinar on this topic now.

FAQs

What is the 3 + 3 clinical trial design for cancer drugs?

The 3 + 3 clinical trial design is a traditional, rule-based method used in Phase I oncology trials to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of a new cancer drug. This design is popular due to its simplicity and ease of implementation in a clinical setting.

How does the 3 + 3 clinical trial design work?

The 3 + 3 design for clinical trials starts at a very low, safe dose and escalates based on the number of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed during the first treatment cycle (usually around 4 weeks):

Initial Cohort: Three patients are enrolled and treated at a specific dose level.

Dose Escalation (0 DLTs): If none of the three patients experience a DLT, the next cohort of three new patients is treated at the next higher dose level.

Dose Expansion (1 DLT): If one of the three patients experiences a DLT, three additional patients are enrolled and treated at the same dose level to gather more safety data. The total number of patients at this level is now six.

Dose De-escalation/Stop (2+ DLTs): If two or more patients (out of either the initial three, or the expanded six) experience a DLT, the dose is considered intolerable. The trial stops escalating, and the MTD is defined as the highest dose level at which no more than one out of six patients experienced a DLT.

What does the FDA think about Bayesian clinical trial designs?

The FDA recently issued a draft guidance, Use of Bayesian Methodology in Clinical Trials of Drug and Biological Products. This approach can be helpful for dose finding trials in oncology and can inform drug development for other therapeutic areas too.

How can clinical pharmacologists and biostatisticians help design clinical trials for cancer drugs?

Certara’s clinical pharmacologists and biostatisticians help design cancer drug trials by determining the optimal dose and schedule for safety and efficacy, using modeling and simulation to predict drug behavior in different patient groups (for example, patients who are obese, pregnant, elderly, or pediatric), and optimizing trial designs to include patients with comorbidities (renal, hepatic impairment), or other factors that might influence drug response. They also contribute by analyzing clinical trial samples, developing study protocols, and providing expertise on characterizing a drug’s PK and PD (including its absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and biomarker activity).

Advanced biostatistics consulting and CDISC-compliant statistical programming

Our team excels in advanced statistical methodologies and adaptive clinical trial designs to help you conduct efficient and cost-effective trials that increase the odds of regulatory approval.

Fran Brown, PhD

Vice President, Global Head, Drug Development ScienceFran has over 25 years of experience with strategic and operational global drug development from early discovery to filing and post-marketing. She possesses a broad knowledge of strategic drug discovery and development, with a special focus on development strategy and the application of model-informed drug development (MIDD).

Blaire Osborn, PhD

Senior Director, Clinical Pharmacology and Translational MedicineDr. Osborn has over 25 years of drug development experience in the areas of clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. She has focused primarily oncology and anti-infectives. Before joining Certara, she was a reviewer in the Office of Clinical Pharmacology, US Food and Drug Administration, in the Division of Cancer Pharmacology, CDER where, she participated in the assessment of multiple dose justification submissions under Project Optimus. Prior to working in the FDA, she was a clinical pharmacologist in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institute of Health (NIH).